In 2022, the Culture & Animals Foundation provided a grant to VINE Sanctuary in Vermont to engage a scholar as an intern. Rebecca Shen, who is undertaking a master’s degree in landscape architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, was chosen. CAF Navab Fellow Victoria Reshetnikov sat down for an interview with Rebecca.

On your website, you indicate your broad interests as a landscape architect “lie in the synthesis of landscape and culture in the era of rapid social shifts happening under climate change,” specifically “in landscapes of multispecies living communities, food production, and climate change mitigation at the community scale.” What stimulated your interest in these particular landscapes, and why is your study of them important?

I believe engaging in these landscapes can combat the feelings of grief and helplessness around climate change. These landscapes can imagine more regenerative and empathetic means of production, relationships to nonhuman others, and community infrastructure. I am inspired by how resilience is generated through day-to-day community actions and beliefs. Climate change solutions are often framed as requiring massive systemic changes in policy and market forces. While this is true, this large-scale emphasis can alienate people from feeling empowered in their own ambit and having a personal, tangible stake. The landscapes we inhabit, cultivate, and produce cultural meaning from should be thought of as places that help individuals and collectives to better navigate a changing, more-than-human world. I believe that design is first embodied in community values and attitudes toward physical and sociocultural environments, which is why I am interested in studying the landscapes in which we directly exercise these values on a day-to-day basis.

What drew you to VINE Sanctuary as a possible focal point for your study?

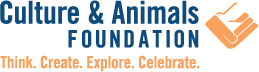

I had long known I wanted to investigate the landscape of a farmed animal sanctuary [see Fig. 1], where refugees of the animal agriculture industry live for the rest of their lives, thereby eluding their fates as mere industrial commodities, laborers, or objects of entertainment. This sets a foundation for practicing and designing more ethical relationships between humans and farmed animals. In search of a sanctuary to explore, I came across the paper “Animal Agency in Community: A Political Multispecies Ethnography of VINE Sanctuary,” which introduced me to the site of VINE and the methodologies of multispecies ethnography. Multispecies ethnography, a more recent branch of cultural anthropology, explores the interspecies relationships between humans and animals and how they engage in and shape political, economic, cultural, and ecological systems together. Its unique application in a study of VINE Sanctuary, conducted by legal and political scholars, sought to uncover the “animal agency in a sanctuary for formerly farmed animals, considering how a careful exploration of dimensions of agency in this setting might inform ideas of interspecies ethics and politics.” [Blattner, Donaldson, and Wilcox, “Animal Agency in Community: A Political Multispecies Ethnography of VINE Sanctuary.”] This place-based study made me curious about how the physicality of a landscape influences interspecies relationships. It also motivated me to adopt the lens of multispecies ethnography for my own fieldwork focusing on the landscape of the same sanctuary.

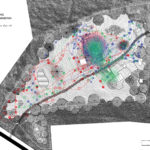

VINE Sanctuary’s ethos of engaging with and respecting animals further reinforced the choice to study its landscape. This sanctuary is a place where human staff members nonchalantly refer to the animal residents as “people,” a vocabulary that underpins each animal’s individuality and personhood. It is a place where its nonhuman residents can intermingle across species lines by sharing play structures, routines, and sleeping enclaves in the forest. The sanctuary has a dynamic topography and is covered in forest [see Fig. 2], which enables residents to interact and exercise agency on the land in ways that are not commonly observed of farmed animals because they are typically not placed in such free-flowing environments. The opportunities that the land provides, as a canvas for the expression of animals’ agencies, became the focus and motivation for my work at VINE.

Your project was to “map the terrain” at VINE Sanctuary to study non-human members’ utilization of shared space. What did that entail, and why was it important to do the mapping?

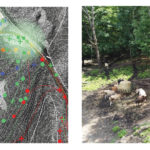

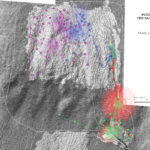

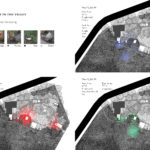

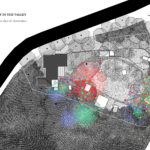

I was inspired to create my own twist on ethnographic methodology when the animal residents gave me clues about how to traverse the landscape. In my first few days of observation, I discovered ways to better maneuver around the woods by following the narrow paths that the cows have paved over time [see Fig. 3]. I was entranced by the nimbleness of the sheep, goats, and alpacas as they climbed over mounds, fallen branches, and boulders [see Fig. 4]. I saw how chickens were actively shaping the ground through their hole-digging and path-paving within the dense vegetation [see Fig. 5]. The movement mapping method was conducted as follows: I traced and mapped the movements and locations of a few selected residents at regular time intervals (such as every 10 minutes) for a total of about five hours per day without breaks. At each time interval, I marked the location of the resident, each denoted by a different symbol, along with the number of which iteration I was at. If the resident had not changed location, I drew a circle around their symbol. I repeated these steps for 30 iterations. I would do this starting at approximately the same time for three to four days in a row [see Figs. 6–9]. This allowed me to observe movement and behavior over time while physically and even socially integrating with the communities I was observing, an essential aspect of conducting any ethnography.

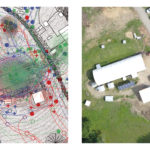

Through this active observation and immersion, I began to understand dimensions of agency that are comprised of individual behavioral tendencies, gathering, space-making, and routines. It was clear that the residents made delineations of space across the landscape. Some examples include assigning certain enclaves in the forest for rest and creating a path network over time to readily access favorite spots in the sanctuary [see Fig. 10, 11]. I read these as acts of agency across the vast and varied landscape, uncovering the residents’ embodied day-to-day experiences and demonstrating the individual and collective ways they have physically and socially found refuge at the sanctuary. Upon tracing their moments of movement and rest alongside them for extended periods of time, I produced a collection of maps that can be used as tools to read and understand their embodied agencies upon the landscape. These maps are also recorded memories of a unique history I shared with the residents.

What did you learn from your experience at VINE that you hadn’t expected to learn?

There were abundant opportunities for learning about the unexpected ways animals engage with each other and with humans. I made initial generalizations and assumptions upon arriving. The first time I ever encountered cows in a forest was on my first day at VINE Sanctuary. Their presence in the wild context of the forest was uncanny; the forest is not where most people imagine cows wandering, foraging, and resting. Having grown up near a rural area in Upstate New York, I am used to seeing cows dotted amongst bucolic agricultural landscapes in my casual roadside passings. However, cows grazing contentedly in the countryside is a staged façade. Most cows in the United States (an estimated 70 percent as of 2019) are raised on concrete, highly concentrated feedlots or factory farms, an intentionally invisibilized landscape that comes into conflict with pastoral associations of cattle geographies. I was taken aback by the rare scene at the sanctuary: here, cows are inhabitants of a forest habitat. I also had preconceived ideas about animal behavior.

I fully expected that given all the land that VINE has to offer to its residents, they would be wandering freely everywhere, all the time, which was not the case. While the residents did wander off to many unseen corners of VINE, many were evidently methodical and intentional with their approach to when and how they experienced the land. I learned there were routines and patterns of engagement with the land that would be insufficient to define solely by species behavior or instinct. Residents’ individual histories, personalities, and perspectives also defined their actions.

Did the animals teach you anything about living in a community that made you think about how humans live in a community?

VINE Sanctuary staff and visitors practice an ethic that fosters an environment that allows animal residents to self-actualize. I tried my best to embody these in my direct engagements with the residents. In many ways, rules of respectful engagement in human society are also practiced with the nonhuman residents at the sanctuary. For example, adult animals are seen as individuals who can make their own decisions and will only be handled for veterinary purposes. It would have been unfavorable conduct for me to approach a resident who showed clear indications that they wanted to be left alone. There was an instance when a cow resident stood up from her nap and shooed me away because my camera clicks were annoying her; this made me aware of the conflict of respecting the personhood of an animal while invasively snapping photographs. Some residents preferred to jubilantly greet me every morning, and other residents wanted nothing to do with me and surely showed it. While I don’t believe we should always be anthropomorphizing our relationships with animals, there seem to be enlightening things we can learn when animals’ social conduct, emotions, and bonds mirror those in human relationships. It grows empathy.

There were values of respectful and empathetic human–animal engagement relationships that VINE Sanctuary’s founders established from the onset. In establishing values for what your community wants to be, decisions can be made on how to delineate space, change the space over time, and welcome new residents.

Do you see VINE Sanctuary as a model—not just as a sanctuary, but as a more just means of living among other animal communities? If so, how? If not, why not?

VINE Sanctuary is recognized by many in the animal sanctuary and scholar communities as a model for practicing an intentional, respectful way of engaging with farmed animals, a specific category of animals who have been commodified. Observing how they engage with newfound rights to flourish, to live in community, and to access the land might provide new opportunities for understanding and modeling new ways to cohabitate with other farmed animals in refuge. There is a growing body of published and in-progress work that looks to the community at VINE for the unique relationships and ethos it embodies. At VINE, there is a well-established set of values that allow human staff members, volunteers, and visiting scholars to be able to put those values into practice.

I believe that animal communities are very place-specific: I do not engage with animals in urban environments or the wild the same way as I did with the residents at VINE. The idea of non-exploitative relations with animals that is embodied at farmed animal sanctuaries can be the foundational value carried into other animal communities. From there, the model of living “justly” would depend on the place, comprising of the whole community of people, animals, and plants.

- Fig 1. Overall Map

- Fig 2. Fieldnotes and Movement Mapping

- Fig 3. Pathmaking in the Commons

- Fig 4. Pathmaking in the Commons (Overlay)

- Fig 5. Dyptich

- Fig 6. Fieldnotes and Movement Mapping in Middle Pasture

- Fig 7. Pathmaking in the Middle Pasture and Forests

- Fig 8. Dyptich and Map

- Fig 8. Pathmaking in the Middle Pasture and Forests (Map)

- Fig 9. Pathmaking Near the Back Hoop Barn and Mounds

- Fig 10. Pathmaking in the Back Pasture & Forests

- Fig 11. Residents Emerging out of the Misty Forest

- Fig 12. Movement in the Valley

- Fig 13. Movement in the Valley (Overlay)