Requiem for Animals, a piece written by composer Keane Southard (2024) for a choir of sopranos, altos, tenors, and bases, and string orchestra, was commissioned by the Brattleboro Music Center (for performance in May 2025 by the Brattleboro Concert Choir, Jonathan Harvey, director) with additional support from the Culture & Animals Foundation and the Eric Stokes Fund, Earth’s Best in Tune. This interview is excerpted from Keane’s prefatory material for the piece’s complete score.

Q: What was the origin of Requiem for Animals?

Q: What was the origin of Requiem for Animals?

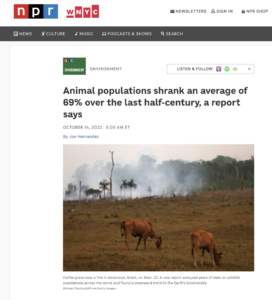

I began composing the work in February 2024 and completed it in late October. The idea to write it came in fall 2022 when I heard a story on National Public Radio about a recent study that found that wildlife populations have declined by an average of 69 percent over the past fifty years, primarily driven by human actions contributing to climate change, including how we produce food, what we eat, and how much food we waste. This huge decline struck me very hard emotionally, especially as I realized that our system of food production takes a nearly unfathomable amount of animal lives as well.

Q: How so?

In essence, as a society we are killing billions of domesticated animals, which is then leading to the deaths of billions of wild animals. This amount of suffering is so immense, yet many people aren’t even aware of it. As a composer, the idea naturally came to me of expressing and conveying the magnitude of this suffering through music, so that more people could be aware of, and reconsider how, we collectively treat and interact with all animals beyond just our pets.

In essence, as a society we are killing billions of domesticated animals, which is then leading to the deaths of billions of wild animals. This amount of suffering is so immense, yet many people aren’t even aware of it. As a composer, the idea naturally came to me of expressing and conveying the magnitude of this suffering through music, so that more people could be aware of, and reconsider how, we collectively treat and interact with all animals beyond just our pets.

Q: Why did you choose a requiem?

Many composers have created requiems to commemorate the dead and lament the loss of life, but these have always been for human life. I thought it was certainly time that animals were memorialized in a requiem as well. This requiem combines texts from the traditional Latin requiem mass with texts from various sources and authors (the Bible, J. Howard Moore, Upton Sinclair, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, as well as some original texts of my own) that deal with how humans treat and interact with animals.

Q: How does the piece utilize the components of the requiem?

The opening Introit (All Beings Are Ends) highlights the commonalities between animals and humans, as we are, after all, animals, too. In the Kyrie (600,000), the choir sings a running estimated tally of how many land animals have been slaughtered for food worldwide since the movement began (based on Faunalytics’ estimate of 73,162,794,213 land animals slaughtered in 2020). This comes out to about 23,200 every ten seconds. I used a more conservative realization of this rate where the choir adds 20,000 to their tally roughly every ten seconds.)

The opening Introit (All Beings Are Ends) highlights the commonalities between animals and humans, as we are, after all, animals, too. In the Kyrie (600,000), the choir sings a running estimated tally of how many land animals have been slaughtered for food worldwide since the movement began (based on Faunalytics’ estimate of 73,162,794,213 land animals slaughtered in 2020). This comes out to about 23,200 every ten seconds. I used a more conservative realization of this rate where the choir adds 20,000 to their tally roughly every ten seconds.)

The longest and most intense movement of the requiem, the Sequence (Dies Irae) explores how we have mistreated animals and the consequences of doing so. It includes an extended scene at its heart from Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, set inside a slaughterhouse. The Agnus Dei (Lambs of God) takes the metaphor of Christ as a sacrificial lamb and extends it to the myriad literal lambs that are killed each day, asking what the meaning of their sacrifice is.

The Lux Aeterna (Those Who Are Gone Forever) asks for eternal light to shine upon our extinct wildlife species, listing thirty-two which have gone extinct primarily due to the impact of human activities. The Libera Me (Which Shall It Be?) asks us, as the undeniable “masters of the earth,” what kind of relationship we will have with the world and its creatures. We have the power to choose: we can continue to dominate and exploit it, or we can be its caring and benevolent stewards. The final movement, In Paradisum (The Voice of the Voiceless) answers this question, proclaiming that we will speak for and protect all the world’s creatures and that this may lead us all, one day, into paradise.