An Interview with Kevin Augustine

Martin Rowe, ED of the Culture & Animals Foundation, talked with CAF 2024 grantee Kevin Augustine of Lone Wolf Tribe about his play “The People vs. Nature,” which ran at La MaMa Experimental Theater from November 7–17, as part of the 2024 Puppet Festival.

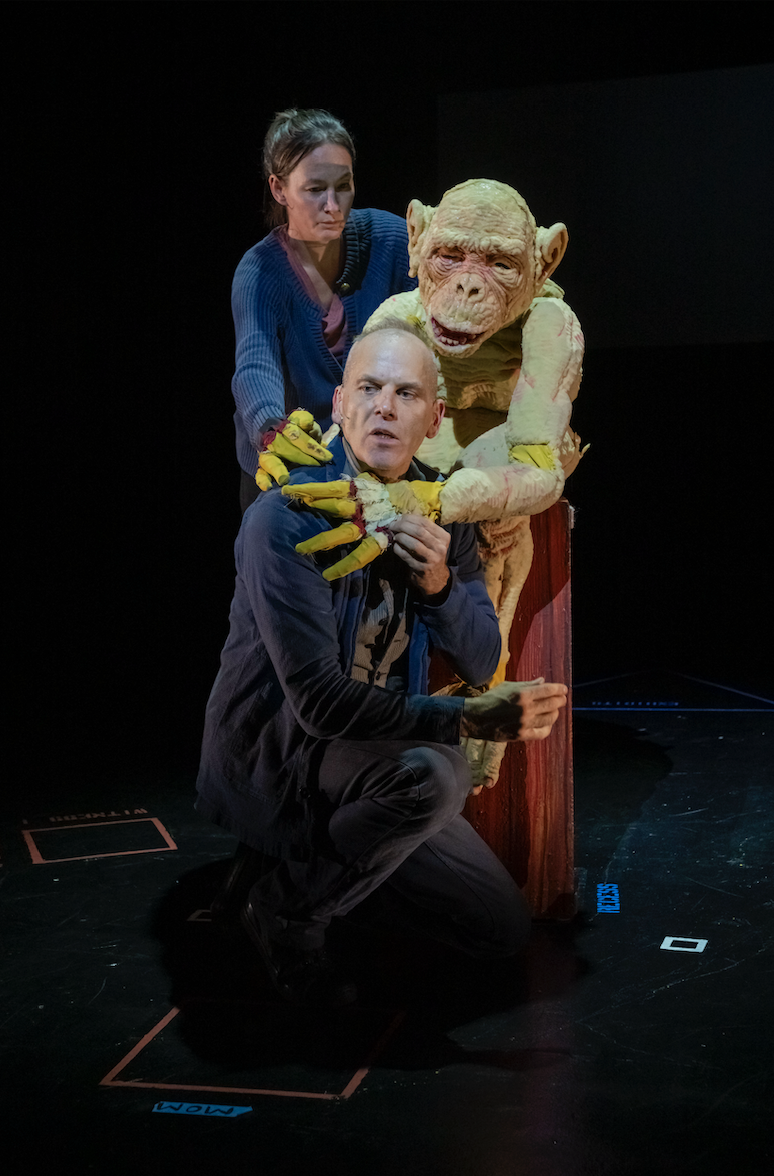

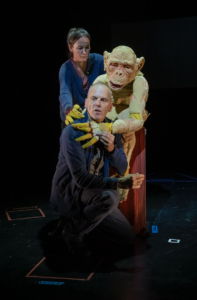

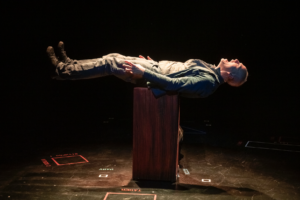

“The People vs. Nature” relates the story of Jerome, a chimpanzee captured in the wild and brought to a medical facility in the United States, where he’s confined and experimented on for almost four decades. His keeper, Terry, is at first hostile to him and the other chimps before he teaches Jerome sign language. Jerome tells his story, which leads to Terry’s change of heart. Terry lands up on death row, where, twenty years later, he recounts the court case in which he and Jerome were involved. As part of the play, Kevin relates his own family traumas. (Photos, courtesy of La MaMa.)

“The People vs. Nature” relates the story of Jerome, a chimpanzee captured in the wild and brought to a medical facility in the United States, where he’s confined and experimented on for almost four decades. His keeper, Terry, is at first hostile to him and the other chimps before he teaches Jerome sign language. Jerome tells his story, which leads to Terry’s change of heart. Terry lands up on death row, where, twenty years later, he recounts the court case in which he and Jerome were involved. As part of the play, Kevin relates his own family traumas. (Photos, courtesy of La MaMa.)

Martin Rowe (MR): How did this story come to you and how has it evolved to where it is now?

Kevin Augustine (KA): There are a couple different points of origin or bits of inspiration that fueled my journey. I don’t remember which came first, because I began the piece directly following my last production, which ended in 2016. I wanted to go back into the relationships with animals and bring attention to suffering in some capacity. I didn’t know yet what the environment was, or who the animal would be. I also was fascinated with true crime and court procedurals and the whole notion of telling a story where you know the outcome up-front. I’ve always been intrigued by courtroom dramas and well-told stories that have both arguments presented, and to leave it up to the audience to make up their mind.

I didn’t want the play to just be polemical or present a strident, activist point of view that was so in your face that it left no room for you to make your own considerations. That was kind of the broad starting point. The part I can’t recall because it happened gradually was the metaphor of incarceration, of animals being denied freedom. That lent itself to a parallel with the human story on death row. Through the motif of incarceration and lack of freedom, I started to look at my own personal story and how that metaphorically resonated for me—such as when we are constricted or imprisoned emotionally or historically in your family. All those bits started to mix.

I’ve had so many script revisions over the years; it’s only in the last few months that my story kept knocking and say, “I think you can weave us in here.” I was afraid of that because I never wanted the play to become self-indulgent and my story take an undeserved focus. So, it took a long while to find the right way to have those three stories intersect.

MR: For me, the personal story worked very well. Because it also intersects with Terry, the human hero or anti-hero of this piece. Where did he come in?

KA: I was intrigued with a transformation of character: where somebody starts at a very definite point and winds up somewhere else. I remember reading a story of a woman who went to a park in China where pandas were confined in very small cages. The woman went up to a panda, who offered their paw, and she saw that people had stubbed out their cigarettes on the paw, because the skin was bubbling and raw. Reading that was heartbreaking, because I couldn’t believe that someone would have that impulse to do that and cause pain.

I don’t know if the woman had a change of heart in that moment, but she offered that story that resonated with me. I used it as the fulcrum to consider where in this story a character could have that moment. We worked hard to try to justify through the puppetry and the choreography that the character could claim this is the moment that changed his life. I wanted him to make a connection, whereas for years he had just done his job and never considered the beating heart that was inside that cage.

MR: How did the creation of the actual puppet shape the story you decided to tell?

KA: In a lot of ways, some not always preferable: because the best part for me in making the puppet is the sculpting process. That’s when it’s the most pure, and I can refine and keep trying to get to the vision I have in my mind. The hard part comes when then I have to stop that, and I’m satisfied with that result. Now I’ve got to open up the puppet and work on the inside mechanics. Because I’m not a natural engineer and haven’t been trained in puppetry (it’s all self-taught), there’s a lot of trial and error with getting the eyes to move and blink, and the lips to curl and the toes to move.

KA: In a lot of ways, some not always preferable: because the best part for me in making the puppet is the sculpting process. That’s when it’s the most pure, and I can refine and keep trying to get to the vision I have in my mind. The hard part comes when then I have to stop that, and I’m satisfied with that result. Now I’ve got to open up the puppet and work on the inside mechanics. Because I’m not a natural engineer and haven’t been trained in puppetry (it’s all self-taught), there’s a lot of trial and error with getting the eyes to move and blink, and the lips to curl and the toes to move.

Invariably, what happens is that the puppet head starts to change, and it takes me a while to figure out how to understand the changes. I’m always surprised by the puppet. I feel like that quote from Michelangelo: that the sculpture is in the block of marble already, and your job as an artist is to release it. Once I’ve released the puppet to that state, I feel like he’s a co-collaborator. A gesture or movement or holding the breath that long: that’s saying something I didn’t intend.

I always kept arriving at a place in the script-writing process where I thought, “Great. It’s done. We’re gonna do this, these 45 pages.” But working with the puppet or improvising, I’d realize that part of the script didn’t work or something else was happening. Because I allowed myself to be surprised and then followed something I didn’t consciously plan or plot, trying out a lot of different options, that added time. But that’s also magic: to see some other part of my inner artist saying, “Let me out, too. You’re not as done as you thought you were.”

MR: I was fascinated by the role the audience played. Have you always utilized the audience as a part of the drama? If so, why do you feel it’s important to sort of integrate a multiple group of people working with this puppet?

KA: I haven’t always worked in this capacity with the audience. The People vs. Nature is the most I’ve ever done it in. I had the idea of wanting to create an empathy experiment and have, if possible, people consider the lives of these animals or these marginalized characters in a way that took a step beyond just being a spectator or a reader of the book. I wanted you to become that character in some way: to feel their heartbeat and their breath. It was an unknown for me whether or not that would work. Would anybody feel anything differently having participated in that way? That was my hope. I also have gotten tired of this separation between actor and audience and wanted to do something that creates collaboration and community and engagement and dialog. That was the best way I could think of attempting to get them on stage.

KA: I haven’t always worked in this capacity with the audience. The People vs. Nature is the most I’ve ever done it in. I had the idea of wanting to create an empathy experiment and have, if possible, people consider the lives of these animals or these marginalized characters in a way that took a step beyond just being a spectator or a reader of the book. I wanted you to become that character in some way: to feel their heartbeat and their breath. It was an unknown for me whether or not that would work. Would anybody feel anything differently having participated in that way? That was my hope. I also have gotten tired of this separation between actor and audience and wanted to do something that creates collaboration and community and engagement and dialog. That was the best way I could think of attempting to get them on stage.

MR: It was fascinating to see the multivalent possibilities that were opened up by engaging the audience members in the process. First, the fact these people were becoming the chimpanzee, and were doing what they could to make the chimpanzee come to life, provided more vehicles than just yourself or the chimpanzee as a puppet to enable them to empathize. Their seriousness and concentration provided a moral component to the response, which I think was interesting: The chimpanzee was somebody to be taken seriously as a collective endeavor to bring this creature to life. Then it further reinforced the extraordinary capabilities of humans to respond and create drama and belief. Even though it was transparently obvious that this was a puppet being manipulated, and you named the puppeteers and asked them to do things, it served to force the audience to think more creatively and empathize and use their imaginations more. I thought that worked incredibly well as a way to make us respond to this puppet as a chimpanzee.

KA: I’m glad to hear that. That was always the hope. I could feel the energy change. I could have performed those scenes just with a lot of rehearsal and professional puppeteers. Maybe it would have been technically more proficient, but there would have been less heart, I think, particularly because I preface those scenes with a story about a little kid at one of my shows who threw down the puppet and said “It’s not real,” and had a very analytical approach to magic or wonder. I contrast that with bringing people in, in hopefully a very gentle way, and introducing them to wonder or magic and the life of this animal.

MR: You also have the character Terry, who has to acknowledge that the chimpanzee is not only asking for freedom for himself or other members of his species, but for all animals—including those raised for slaughter. In the play, you preface your description of this by telling the members of the jury (which is how the audience is conceived) that you’re not going to show graphic images of animal slaughter. How did you go about making that esthetic choice and making the judgments about what to show, what not to show, and how to communicate it to the audience, both through yourself and through Terry as a character.

KA: It was tricky, because even while I was performing it, a collaborator of mine’s family came. She received feedback that a forty-eight second clip I show containing real footage of two steers going into the slaughterhouse was too much. She said I was making people uncomfortable and jeopardizing the dramatic arc of the play because the audience was checking out. She said I should cut it, and if I needed it, to just talk about or explain it. She also had the caveat that one of her friends was upset about it. “He’s practically a vegetarian,” she said—meaning that he was one of the good guys.

KA: It was tricky, because even while I was performing it, a collaborator of mine’s family came. She received feedback that a forty-eight second clip I show containing real footage of two steers going into the slaughterhouse was too much. She said I was making people uncomfortable and jeopardizing the dramatic arc of the play because the audience was checking out. She said I should cut it, and if I needed it, to just talk about or explain it. She also had the caveat that one of her friends was upset about it. “He’s practically a vegetarian,” she said—meaning that he was one of the good guys.

I kept the clip in because I felt I was already giving the audience the least. I’ve seen a lot of the harshest stuff and have tried to show my family members the truth of what’s really going on behind the cellophane meat. But for my play, I decided I had to ride a different line. I wanted to present both sides of the argument and to create a tension in the audience/jury to make them uncomfortable, and the system to prevail and say, “You’re not going to be able to show what you want. You can only show this much.” So, I wanted the audience to feel relief: “We’ve been spared that. Oh, you’re just going to show us forty-eight seconds? Okay.” I think those forty-eight seconds make the point that these animals are no different than you if you were going to be slaughtered in the next then seconds. They’re terrified. They want to live. They’re trying to escape. I find that heartbreaking. I thought, “C’mon! You can sit through that. Especially if you care about the character Jerome.” “Okay, for you, I’ll do it.”

I had to build up that relationship of care for the audience to swallow it a little easier.

MR: That’s the perennial issue you face as an animal activist who is trying to communicate something that is “inadmissible evidence,” as was the case with the trial here. Tell me about the passage about the pig jumping from the truck in China. How did you feel that fitted into that evidentiary process you were creating in the play?

KA: My colleague said I should cut that as well! But it’s just so clear to see the motivation and intention and thought process of this pig—this animal is trying to change their situation. He’s on a truck; he doesn’t know where he’s going; no doubt it’s not a pleasant journey. He’s trying to say, “I want out.” He makes a choice to jump off that truck to his own detriment; he hits the street hard and rolls.

KA: My colleague said I should cut that as well! But it’s just so clear to see the motivation and intention and thought process of this pig—this animal is trying to change their situation. He’s on a truck; he doesn’t know where he’s going; no doubt it’s not a pleasant journey. He’s trying to say, “I want out.” He makes a choice to jump off that truck to his own detriment; he hits the street hard and rolls.

I was curious about the interpretation of that and how the defense would say, “A pig fell from a truck.” And the chimp uses sign language to say, “Well, your honor, he jumped.” Very different things. I’m surprised people were still saying, “That’s too much, that’s too much.” But that’s the whole point of trying to get you to consider that these animals have a will to live, and they’re being deprived of that in torturous ways. Here’s a very clear indication that the pig is jumping for freedom, or at least he would hope.

MR: Toward the end of the play, Jerome becomes a kind of prophetic figure, which then catalyzes our response to Terry’s decision to, we assume, set the lab on fire, which will ultimately kill the chimpanzees and the warder. I got the feeling that what happens is deliberately vague.

KA: Yes. Different people can decide whether or not he’s guilty or innocent. I wanted to highlight how many people behind bars and who go to their deaths are innocent. Up to their last breath, they will try to convince you otherwise. And you don’t always know: until maybe DNA evidence appears later and they’re released, or posthumously they’re found to have been innocent. I wanted to show that friction in a character who claims he is wrongfully accused, because it happens way too often: 120,000 out of two million Americans are thought to be wrongfully accused. So I’m okay with that ambiguity, because sometimes I don’t even know: Did he do it? Did he not do it?

MR: I was interested in its ambiguity because in some ways the play is about unacknowledged violations and violence, including in your own life, and the responsibilities and blame associated with the accidents that happened with your father and your sister, and your mother’s reaction to your grief. There are all sorts of unjustified punishments and confinements there. I was happily discomfited by my lack of clarity over who was to blame and what actually happened. I imagine that there would be people who wanted more. Did you mean the ambiguity to be a function of your desire to destabilize assumptions about guilt and innocence, good versus bad. For instance, chimpanzees being confined, bad; animals we’re going to eat being confined; okay.

KA: In my pursuit of the story, I wanted to show that conflict between the two characters and what they’re going towards. Terry says, “Jerome changed my life; I want to save his.” So, he’s very myopic in his pursuit of one individual’s freedom. Not until he becomes incarcerated and has the same experience of Jerome does he say, “Now I get the bigger picture.” Jerome was too symbolic to free just him; after all, the president pardons just one or two turkeys on Thanksgiving. So Jerome is thinking outside of his box, as it were. And not just the other animals, but he sees the migrant workers and the prisoners, folks whose freedom is deprived unjustly. I like that.

KA: In my pursuit of the story, I wanted to show that conflict between the two characters and what they’re going towards. Terry says, “Jerome changed my life; I want to save his.” So, he’s very myopic in his pursuit of one individual’s freedom. Not until he becomes incarcerated and has the same experience of Jerome does he say, “Now I get the bigger picture.” Jerome was too symbolic to free just him; after all, the president pardons just one or two turkeys on Thanksgiving. So Jerome is thinking outside of his box, as it were. And not just the other animals, but he sees the migrant workers and the prisoners, folks whose freedom is deprived unjustly. I like that.

I don’t know how successful it was, but I needed to have a conflict between the two of them, even though they love one another. Jerome is saying to Terry, “No, you gotta think bigger.” And Terry just thinks, “You’re gonna screw up our case. The jury doesn’t want to watch cows and pigs get their throat slit. Don’t show this garbage.”

Here’s where I didn’t want to be so ambiguous in the presentation of the puppets. A lot of times, folks want to lean heavily into realism and give the puppets fur and glass eyes. I deliberately wanted to keep them raw; the foam is yellow to remind us that this is a puppet, an avatar, a symbol: “Don’t let your heart break too deeply over this puppet’s fate. Take whatever you’re feeling, and then keep thinking about it after you leave the theater.” This is a play that’s trying to get you to feel but also to think.

That was the point of Jerome’s argument. It’s easy to fall in love with this chimp. It’s easy to not feel complicit in any of his pain, because he’s never on our menu. But he’s saying, “I’m no different than the pig and the cow and the migrant worker and all these other individuals that you are complicit in. And you can make a difference in lessening their suffering if you become aware of the choices you’re making.”

MR: Where or how would you expect The People vs. Nature to develop? Or is this it?

KA: I imagine it’ll develop more after I look at the multiple nights that we videotaped the show and chart the different evolutions and attempts with choreography and cutting or adding lines.

But it is hard to put on this show, and I was lucky enough to have it presented at La Mama. I was going to have it presented outside the festival, but I would have had to carry all the expenses that the festival otherwise covered. And I couldn’t afford to do it on my own. That’s the biggest challenge: finding a space that is available, and paying for it and the marketing. Beyond New York, La MaMa is hopeful that a puppet festival in Chicago might see the merits of this show in January. I’ve been performing a lot more in Europe, particularly in Eastern Europe. And I’m thinking how I can best present the translation: Is it an audio? Because I really am set on wanting to keep performing it for sure. It’s just much easier within a festival circuit, because they’ll cover the logistics.