Isa Leshko is an American fine art photographer whose work focuses on animal rights, mortality, and aging. Her collection Allowed to Grow Old consists of breathtaking portraits of elderly, rescued farmed animals living in sanctuary. It has recently been turned into a book, with essays and photographs from Farm Sanctuary’s co-founder Gene Baur and curator Anne Wilkes Tucker, and a foreword by the author Sy Montgomery.

“I began this series shortly after caring for my mom, who had Alzheimer’s disease,” writes Leshko. “The experience had a profound effect on me and forced me to confront my own mortality.” She continues: “I am terrified of growing old, and I started photographing geriatric animals in order to take an unflinching look at this fear. As I met rescued farmed animals and heard their stories, though, my motivation for creating this work changed. I became a passionate advocate for these animals, and I wanted to use my images to speak on their behalf.”

Leshko started her project after meeting an elderly Appaloosa horse named Petey in 2008 at Winslow Farm Sanctuary. She showed some of the photos from the farm the following year, and the reviews were “overwhelmingly enthusiastic.” She adds: “A few people even cried when they saw the images.” It was then she realized she had to make it a long-term project. She spent the summer of 2010 researching farm sanctuaries in the U.S. and looking at art relating to aging, portraiture, and animals.

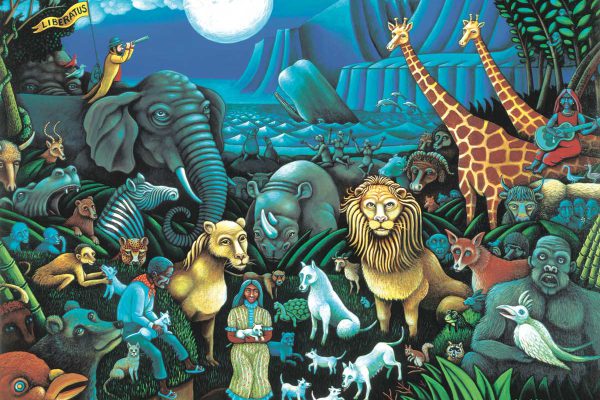

Each portrait in Allowed to Grow Old is accompanied with a brief biographical note revealing the unique story and personality of the animal. Leshko hopes that people who read the book might “stop to consider these animals’ lives and recognize that they’re individuals with unique personalities and emotions. They are not commodities.”

Leshko is aware of the dangers of exploiting the animals by taking their portraits. “When I photograph animals, I meet them on their terms, in their own environments, with minimal equipment, kneeling on the ground next to them. By doing so, I am trying to respect who they are as pigs or turkeys or cows.” She continues: “I actually think that photographing an animal in a studio setting is similar to placing her in a zoo. In both scenarios, an animal is removed from her natural environment and placed in an environment optimized for human viewing.”

Such concern extended to the editing process. “When editing my images for my book,” she says, “I carefully considered whether the images I selected were respectful to the animals I had photographed. Many of the animals I met had lost many teeth and drooled a lot. I wrestled with whether to include drool in my images or to edit it out in Photoshop or choose an entirely different image. I decided to include it in my images because I did not want to impose anthropocentric norms on these animals. I wanted to respect the fact that my subjects are non-human animals and are not humans in fur and feathers.”

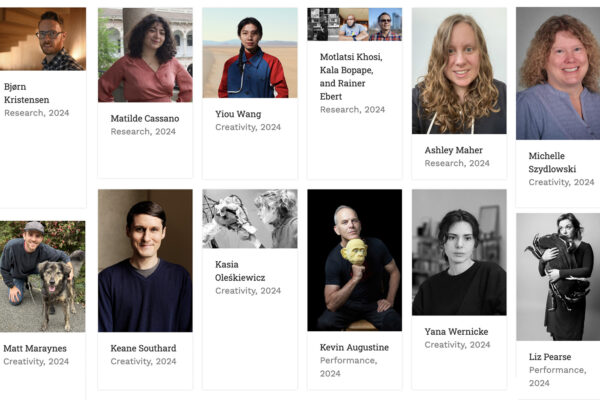

Leshko acknowledges how much work still remains to be done to show how animals are depicted, especially in photography. “Animals appear often in contemporary photography. All too often, though, animals are used as metaphors or as props in these images, which only serves to reinforce speciesist stereotypes about these animals. It is considerably rarer for animals to be photographed as individuals worthy of moral consideration. Our understanding of the ethics relating to photographing marginalized populations has thankfully evolved since the days of Edward Curtis,” she says, referring to the early-twentieth-century photographer of Native Americans. “[The Culture & Animals Foundation] is working toward the day when artists and curators will have a similar appreciation of the ethics relating to the depiction of animals in art.”

Leshko received a CAF grant to help with Allowed to Grow Old. “I was so excited when I found [CAF]. In the art world, animal-themed artwork (especially photographic art) is often dismissed as being too sentimental. Although there are numerous grants for photojournalism and documentary photography, most of these foundations only fund work with a humanitarian focus.

Many high-profile portraiture competitions explicitly exclude animal-themed work,” she continues. “If you are an artist who creates portraits of non-human animals, finding funding for your work can be quite challenging. I am tremendously grateful to CAF for the funding you have provided and also for the ongoing support and visibility you have given my work. I greatly respect that CAF understands that art and scholarship have the power to transform the way society views and treats non-human animals.”

Leshko sees her work with farmed-animal photography continuing: “As a spin-off project, I want to return to create portraits of each animal when they reach the average slaughter age for their species to illustrate that they are still just babies. Juxtaposing these portraits with my elderly farmed animal portraits will be especially powerful.

“I am grateful for the outpouring of love and support that I have received for this work,” she says. “I am deeply touched that my work has affected people on such an emotional level.”