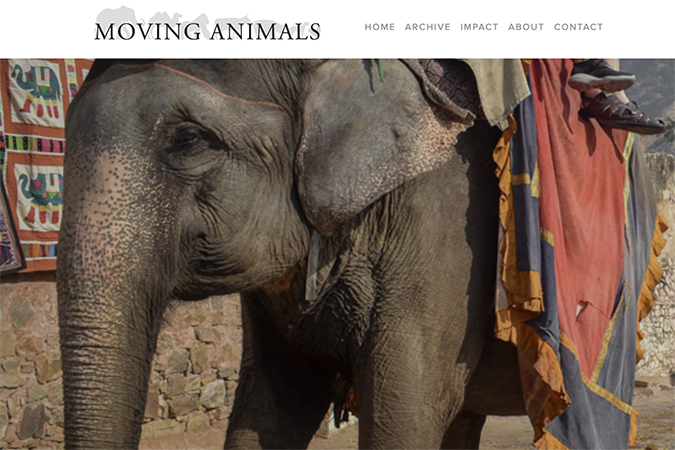

Paul Healey and Amy Jones received a joint grant from Culture & Animals Foundation in 2018 to curate an archive of free-to-use images of animals, while traveling the globe with the aim of raising awareness about these species and their plight. Their project, Moving Animals, launched its official website on March 19, hosting a digital photo library of domesticated, feral, and abandoned animals all over the world.

“Our journey with the Culture & Animals Foundation began thanks to a simple tweet by a previous grantee. Looking back, we feel that this was a fitting beginning, as our project itself focuses partly on the effectiveness of social media to advocate for animals,” says Jones. Visual media has become an important part of the animal advocacy movement. By making images easily accessible, it helps people share stories far and wide at the simple click of a button.

Healey and Jones have astutely realized that presenting their content in a variety of media has made it more effective and accessible. In addition to producing photo and video content, they’ve also added their own independent, investigative research in order to further contextualize their work.

“We’ve produced free-to-use videos with our footage, written press releases directly for news desks, and even researched and conducted our own investigations to substantiate and give additional weight to our photographs,” Jones adds. “Of course, all of these practices stem from the original visuals we capture, so the essence of our project does lie first and foremost in photojournalism.”

“A picture is worth a thousand words” is a well-known maxim, but those words are even more resonant in the world of animal advocacy. Photographs and videos are most popular media right now. The role of photojournalism in the animal rights realm is to reveal the deep, systemic violence that is either hidden or so normalized that people are either ignorant or willfully turning a blind eye to it. To this point, Jones notes, “Animals cannot speak our language, they cannot say ‘stop’ or ‘no,’ and because of this, we can choose to ignore them.”

This is a central tenet and inspiration behind Healey and Jones’ work: speaking for those who are ignored. Their photojournalism doesn’t just communicate the circumstances of the individual animals they document, but opens up a wider consideration and conversation about the ethics and philosophy that govern how most people view animals, doing so in a way that the written word often struggles to accomplish.

“The chicken waiting to be slaughtered may not be able to tell us that she values her own life, but a photograph can show her fear and her fight to avoid the blade,” explains Jones. “Photojournalism helps to bridge the gap between the animals forced to stay silent behind closed doors, and the consumer who is unaware of the suffering in every animal ‘product’ that they consume.”

This is not to say that the written word is without value, both to Healey and Jones’ work in specific or animal advocacy in general. Being in the trenches of oppression can take its toll on people who dedicate their lives to documenting it and, in many cases, it is these very instances—the most dire, intense narratives surrounding animal welfare—that require thoughtful, provocative writing, as advocates are often prohibited from photographing or filming animals in these situations and environments.

When asked about the most challenging experience they’ve faced in their travels, Healey and Jones describe visiting India’s “leather towns”; Indian leather accounts for up to 13 percent of the world’s total production of skins. Although they were able to visit and tour three leather processing farms, Healey and Jones were unable to shoot or film on their premises due to strict no-camera rules.

“What we witnessed there was terrible, for both humans and animals: in two out of the three leather factories, we saw clear abuses of human rights,” Jones recalls. “Workers had no protection for their hands or lungs as they worked with dangerous tanning chemicals for hours on end and thousands of animal skins were stacked around the factories, some still containing the partly severed heads of donkeys, cows, and other animals. The images are still branded into our own minds, but we are unable to show what we saw to others.”

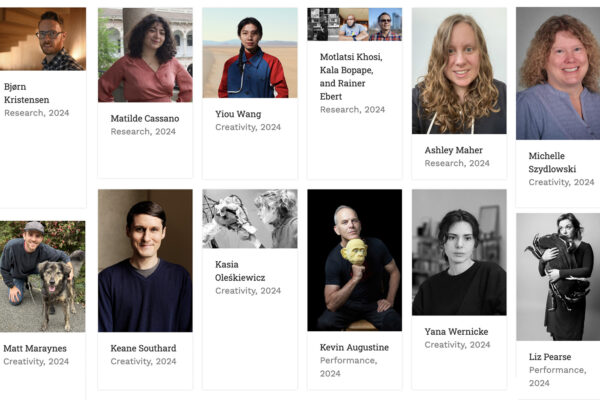

Even before receiving their grant, the Culture & Animals Foundation had a profound impact on Healey and Jones, orienting them toward the work that ultimately earned them their grant last year. When asked about their inspirations, they are quick to mention a host of CAF notables and grantees.

“Jo-Anne McArthur of We Animals, due to her talent and never-ending dedication to animal activism,” Jones says of her personal influences. “Paul said he had taken a module entailed ‘Animals, Humans, Writing’ taught by Dr. Derek Ryan. It was here where he discovered his now-favourite theorists and writers including [Jacques] Derrida, [CAF Advisory Board member J. M.] Coetzee, and of course, [CAF Co-founder] Tom Regan.”

The recent launch of MovingAnimals.org means that Healey and Jones’ content is now readily available to news and advocacy organizations, independent activists, and social media content creators. The site’s archive has a growing collection of over 500 free-to-use images and interested parties can also request video footage. In addition, visitors can look at how Healey and Jones’ footage, which boasts over six million views and has been translated into six languages, has been effectively utilized by international media and advocacy groups.

“It’s our hope that our visuals will be used to illustrate news articles, be shared with quotes on social media, and be used as campaign resources for NGOs,” says Jones. “Part of what drove us to start Moving Animals was the belief that powerful visuals and effective storytelling have the power to change mindsets, and so every view of our work holds the promise to make the world a kinder world for animals, one person at a time.”

You can follow Moving Animals via its official website, and on Facebook and Instagram.