CAF Associate Brooke Rucker reflects on listening to her grandfather, Tom Regan, in an interview from 2001, produced for the Recording Animal Advocacy Oral History Project.

I did not realize I remembered what my grandfather’s voice sounded like until I pressed play on the recording of his interview with Charles Hardy. Tom Regan’s tone and cadence were exactly how I recall them, although I remember his voice more vividly when he would help me and my cousins pick the perfect pumpkin for Halloween, or as he would call out the answers in Jeopardy! Despite all his intelligence and insight, he rarely spoke to me about anything to do with animal rights, which made sense for the time. My younger self was more preoccupied with the coloring books he and my grandma kept behind the couch, and I did not realize all the education that I could have gained from him until it was too late.

The fact that I was never able to engage in distinctly philosophical discussions with him made listening to this interview feel all the more special, as I am now able to comprehend and agree with the valuable adages he provides during this extensive piece, provided by Columbia University. His words surprised me a few times in this interview, namely when he brought up the institutions that lie behind the evils we see in today’s world, and how these institutions are truly the ones to blame. Even though the interview was recorded in 2001, these same sentiments seem more relevant than ever, with a select few people controlling almost entire industries. Whether with food production companies like Tyson Foods Inc. or delivery services such as Amazon, our society continues to be dominated by corporations that support the use and abuse of animals.

Inevitably, I wonder if my grandfather would be disappointed in the progression of our society. At one point during the interview, he discusses the second March for the Animals that took place in 1996, but with a critical perspective due to an unfamiliar sense of commercialization, as manufacturers lined the streets during the march trying to sell certain products. He recalled that these companies were not present during the first event (in 1990), and that, ultimately, the failure of the movement was strongly linked to this new profit-oriented attitude. It seems as if his main issue with commercialization goes back to another one of his major arguments about the detriments of our society’s mindless consumer culture, and how animals get caught up in it. Evidently, this remains—or has grown—as a problem in today’s world.

It is difficult to be fully informed about and aware of the food we consume, of where we purchase our clothes, of the products we buy; yet there is a sense of obligation to continue the cycle of consumption. The true source of this culture is elusive, but I believe that my grandfather was as close as anyone in saying that these institutions are the instigators of our present way of life, and that they are the true root of evil within our world—or at least, evil from an animal rights perspective.

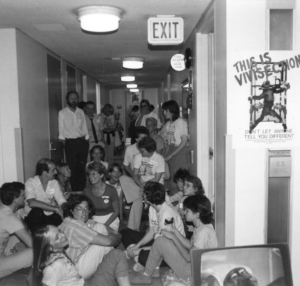

But the interview was not only about the negatives of our world. He also recounted a couple of his life experiences, one of which my own mother was involved in. This was the famous National Institutes of Health (NIH) sit-in (left) against animal experimentation in 1985, in which about a hundred people occupied the eighth floor of the NIH offices, resulting in funding cuts for the animal lab in question and an investigation. It was a peaceful protest that marked an important shift in the animal rights movement, demonstrating that real change was possible through civil disobedience.

An equally significant section of the interview had to do with his writing process for his major work, The Case for Animal Rights. He described a feeling of pure excitement in writing this book, even bringing a pen and paper to write down any ideas or notes while on his long runs. Both of these experiences made an impression on me, for different reasons. With the NIH sit-in, hearing success stories for the animal rights movement is almost always heartening. Events like these show that change is attainable, even when it seems impossible in the face of daunting authority. On the other hand, hearing about his experience in writing The Case for Animal Rights was inspiring from an artistic perspective. His descriptions of the happiness and motivation that he experienced while writing are feelings that artists of any kind strive for.

I often think back to any regrets I have about the end of my grandfather’s life—if I could have been more understanding, more helpful. While I don’t necessarily feel as if I should have changed any of my actions, I do wish that during that period of my life, I had been more mature so I could have spoken to him about topics like those that he covered in this interview. Despite these sentiments, I feel thankful that I am still able to experience his words after his passing, and that his beliefs are preserved in books, videos, articles, archives, the Culture & Animals Foundation website, and in the memories of my family members.